He’s only 14, but Samer* is already making difficult choices and sacrifices just to get a basic education. Living in a tent in Lebanon after fleeing the fighting in Syria with his mother and brother two years ago, Samer leapt at the first opportunity to return to any kind of schooling.

He borrowed money for transport, and when it wasn’t enough walked for miles in pouring rain to attend remedial classes and life-skills training provided by World Vision — the closest he can get to an education in a host country struggling to cope under the weight of more than one million refugees from the conflict.

“I know it’s not a school, but I learned so much,” he says, speaking of the classes. “I love learning. I wish I could live in a school.”

He’s not alone. As the conflict in Syria approaches its fifth year, the education figures are startling — 78 percent of school-age Syrian refugees in Lebanon are not in school. In fact, there are more Syrian children of school age in Lebanon than there are Lebanese children enrolled in classes.

A world away in Burundi, six-year-old Diella was desperate to go to school but couldn’t. Not because her family didn’t value education, and not because she was too poor.

Diella couldn’t go to school because in Burundi children don’t start primary education until age seven.

This wasn’t good enough for Deilla’s mother, Nathalie who tried again and again to convince the school that Diella should start a year early, but was unsuccessful.

The reasons there are 58 million children like Samer and Diella unable to access the education that is their right — highlighted in last month’s report from UNICEF, Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All — vary greatly. But they are not impossible, or in some cases even difficult, to fix.

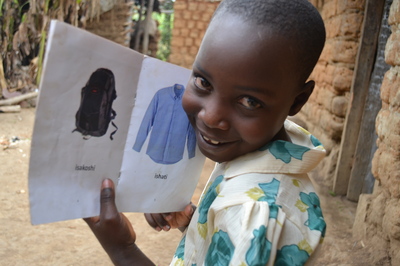

After her daughter was refused entry to school, Nathalie took Diella to a Literacy Boost reading camp, a World Vision-Save the Children program that helps strengthen reading skills in young children in- and out-of-school.

When Diella turned seven, Nathalie brought her back to the same school to register for classes. The registrar hesitated again; the school had limited capacity and older children were being prioritized for attendance. Nathalie insisted that her daughter be tested for her literacy skills, and the head teacher was impressed that Diella could read and write and admitted her into the school.

Diella’s story has a happy ending: she attends school regularly and is first in her class. But the UN report paints a dismal picture of what life could have been like for Diella if she had remained out of school.

Children not in school are particularly vulnerable to exploitation, violence and discrimination. They are more likely to be forced into dirty, dangerous or degrading work or into early marriage. Children with disabilities, girls in some cultures, and children who live and work on the streets, are at even greater risk. Despite knowing this, one in ten children is still out of school. It’s almost staggering that this is the case, in 2015. Failing to ensure that all children are able to access adequate education will have repercussions for generations.

Getting children into school is just the beginning. In partnership with Save the Children, we started the Literacy Boost program not only to reach those out-of-school, but also to help some of the 250 million children who are in school and not learning basic literacy skills.

This approach is working. In Ethiopia, after only six months of Literacy Boost, 35 per cent of students became new readers, compared to 19 per cent in comparison schools. In Malawi, where girls often struggle to succeed in school, they showed significant improvement in literacy skills through Literacy Boost: equivalent to an additional two to four months of instruction.

We can build more schools, buy more pencils and fill classrooms with books, but if we don’t work in partnership with national and local governments, teachers, parents and communities, to help children learn in- and out-of-school, we won’t see education change lives in the way we know is possible.

Literacy unlocks human potential and is the cornerstone of development. It leads to better health, better employment opportunities, and safer and more stable societies. As leaders discuss the post-2015 development goals that will replace the Millennium Development Goals at the end of this year, we need them to ensure educational services are expanded. We need them to do this so that Diella and millions more don’t have to fight so hard to access this right they are entitled to – and deserve.

By Linda Hiebert