June 16, 2015

People across the developing world are using cell phones to pay for everything from taxes to taxis.

An estimated 2.5 billion adults do not have access to banks. Unsurprisingly, they are among the world’s most destitute: According to a report released by the World Bank and other development groups, about three out of four adults living on less than $2 a day, from farmers in Tanzania to slum-dwellers in India to seamstresses in Bolivia, lack an account with a formal financial institution.

But many of these people do have cell phones. Globally, there are some 7 billion mobile-phone subscriptions, up from about 2 billion in 2005. Beyond simply helping people stay in touch, the devices are being used to report fair-market prices for crops, document wartime atrocities, and even track the spread of disease. The technology is also reinventing a key tool for economic growth: banking.

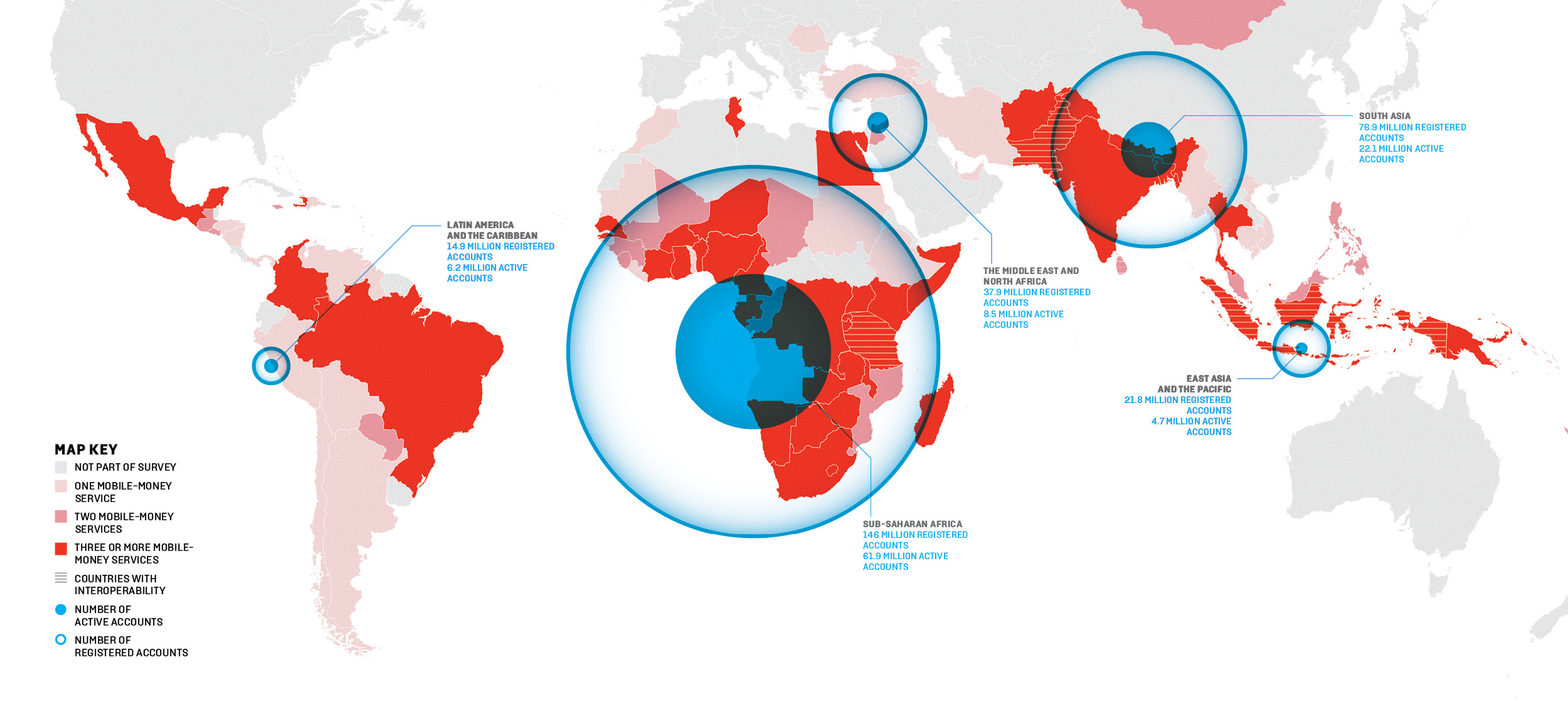

In countries across the world, mobile operators—think the equivalents of Sprint and Verizon—now offer services that enable individuals to transfer cash via text message. In 2014, according to the international mobile-carrier trade group GSMA, there were 255 mobile-enabled electronic money services working in 89 countries, and nearly 300 million mobile-money accounts. The trend is particularly significant in Africa, where in at least 15 countries mobile-money accounts now outnumber formal bank accounts. With even the most basic cell phones, users can pay taxes and taxis, send remittances to faraway families, and even receive salaries and government subsidies.

To be sure, it’s still the early days for this booming industry. Developing economies remain dominated by cash. But mobile money has in many ways already started to reshape the very architecture of financial services for the better.

THE COSTS OF EXCLUSION

Mobile money isn’t just convenient; it’s a boon for financial stability. While mobile banking offers formal saving opportunities, it also provides loan options to the 55 percent of borrowers in developing countries who have traditionally relied on friends, neighbors, or, problematically, local moneylenders. In rural areas in the developing world, informal predatory lenders offer loans at exorbitant rates. In India, for example, a 2010 government report indicated that some farmers using unofficial sources were paying interest rates above 30 percent.

Types of Mobile-Money Transactions by Market Volume and Market Value

Number of Live Mobile-Money Services Worldwide (2004-2014)

THE MODEL: M-PESA

M-Pesa, developed by international telecom giant Vodafone, is the poster child for mobile money’s ascendance. Started in Kenya in 2007, it is now the country’s largest service, with some 15 million account holders. But what started as a simple mobile transfer service—individuals could send money to other individuals—has evolved to include a whole range of financial services, allowing people to pay bills, deposit savings, and even purchase health insurance. M-Pesa is now in 10 countries, including Tanzania, India, Egypt, Fiji, and Romania.

FUTURE CONNECTIONS

Despite the proliferation of accounts, mobile banking has a long way to go before overtaking traditional financial institutions. One reason is a lack of integration. Mobile-money operators have long restricted users, even within the same country, from transferring cash to and from accounts run by competitors. That means a farmer using Vodafone cannot use mobile money to pay a seed supplier who subscribes to Orange. But this could soon change: In Tanzania, account holders with Tigo, one of the country’s largest mobile-phone operators, can now transfer money to and from Airtel and Zantel accounts. And on a larger scale, in April 2014, nine operators offering mobile accounts in nearly 50 countries in Africa and the Middle East committed to moving toward integrating their services. It’s a tentative but critical first step toward a truly international mobile-money system.

TRACKING CORRUPTION

Some policymakers see mobile financial services as a tool to help root out graft. In Afghanistan, for instance, where lawmakers often take kickbacks on government contracts and police threaten arrest if a bribe isn’t paid, the U.S. Agency for International Development is betting on electronic trails for financial transactions: It has allocated millions of dollars to boost a range of mobile operators in the country. According to a 2010 U.S. Institute of Peace report, the expansion of the service by Roshan, just one of the operators in Afghanistan, could save more than $60 million lost annually to corruption and banking fees.

Source: Foreign Policy