March 9, 2015

HUGE jars of iridescent yellow liquid glow on almost every street corner in Cotonou, the commercial capital of Benin. Taxi drivers pull over to fill up their cars using a hose and funnel. Proper petrol stations, by contrast, stand empty. “It’s cheaper this way,” explains a taxi driver, as he tanks up using the unofficial method.

The origins of this black market lie less than an hour’s drive away, across Benin’s eastern border, in Nigeria, where imported fuel is sold at subsidised rates and the price paid by drivers is capped, thus generating a massive trade in illicit petrol. Known in Benin as kpayo, it is a third cheaper than the legal stuff; 80% of the petrol in Benin’s cars is said to have been smuggled in. Of the 2m or so barrels of oil pumped out of wells in Nigeria each day, as many as 400,000 are reckoned to be stolen, often with the connivance of politicians.

Some argue that the black market does at least provide jobs. But Daniel Ndoye, a Senegalese economist at the African Development Bank in Cotonou, says that on balance it holds back Benin’s development: “It causes huge loss of revenue for government, which affects infrastructure development and the business climate.” Illegal fuel can be dangerous: people have been burnt alive in accidents with it.

Sabotage of Nigerian gas pipelines also upsets the country’s neighbours. Attacks have been increasing in the approach to Nigeria’s presidential and general elections expected (after a delay) later this month. Some say that opposition supporters want to create a “politically motivated disruption”, reports Malte Liewerscheidt of Verisk Maplecroft, a risk consultancy.

Ghana is another country in the region that has been hurt by Nigeria’s shortcomings—in the supply of gas. Nigeria has consistently failed to fulfil a contract to supply its neighbour with 120m cubic feet a day. In fact, it has recently been providing as little as half that amount, causing Ghana to fall short by as much as a third of peak demand for electricity every day.

Fuel-smuggling and gas hold-ups are not the only way in which Nigeria affects its region. Since its population, of 170m or so, and its economy are both by far the biggest in Africa, it has a huge influence in almost all spheres. Some of it is beneficial. With annual growth of over 6% in the past decade, it lifts the economy of the entire region. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which embraces 15 countries, relies on Nigeria for the lion’s share of its money. In the past decade or so Nigeria’s armed forces and its diplomatic muscle have helped end wars in Liberia, Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone.

Yet Nigeria is also an exporter of insecurity, much of which can be traced to dizzying levels of corruption and political inertia. “Corruption is so pervasive in Nigeria,” said a report in 2011 by Human Rights Watch, a New York-based watchdog, that “it has turned public service…into a kind of criminal enterprise”—with spillover effects across the region.

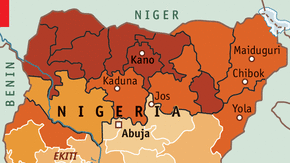

The inability of Nigeria’s army to defeat or even contain Boko Haram, a violent Islamist group that has been trying to set up a caliphate from its base in the north-east, has also hurt the region, by letting the rebellion seep into Chad, Niger and Cameroon. This, too, is partly down to corruption. While Nigerian generals have pocketed vast chunks of the military budget, ill-paid, poorly equipped and demoralised soldiers have been either unable or unwilling to fight the enemy.

Piracy is another growing regional problem that can be blamed largely on Nigeria’s inability to police its oily creeks in the Niger delta. Since 2012 the Gulf of Guinea has replaced the waters off Somalia as the world’s piracy hotspot. Ships along the coast between Ivory Coast and Angola have been attacked. Ghana’s offshore stretch is now particularly exposed, says Harry Pearce of Ambrey Risk, a British consultancy. Piracy may cost the region as much as $2 billion a year.

Nigeria also hurts the region with its protectionist trade policy. It bans the import of hundreds of goods, from cement to noodles. Yet Nigeria has failed to industrialise. The biggest beneficiaries may well be businessmen (often politicians) with ties to government. With friends in the right places, Nigerian supermarkets and posh shops can stock up with prohibited imports such as exotic beer and shoes.

Meanwhile a new regional tariff system, altered at Nigeria’s insistence, levies 35% on certain imported goods, almost twice the highest level proposed by other west African countries. The International Growth Centre, part of the London School of Economics, reckons this trade policy could mean that the average level of tariffs on goods imported into Liberia, for instance, could double. Not a good way to make other west Africans love Nigeria.

Source:Economist