THE LOWDOWN

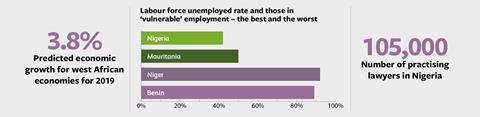

Post-Brexit, businesses are exhorted to redouble efforts to trade with ‘the rest of the world’. The economies of west Africa would seem to be an ideal target – resource-rich and populous, and actively seeking outside investment and expertise to build the infrastructure that could unlock further potential. That the region’s largest economy Nigeria retains its common law tradition would seem to give UK-headquartered law firms the edge in seeking part of the economic action. But this is no ‘gold rush’. The region’s large legal profession is fragmented and protectionist. Its 16 Francophone jurisdictions are not impressed with a London postcode. China has secured trophy investment projects, and the security risks are often high. Yet these competitive markets are worth paying attention to.

There is no disputing that west Africa offers new fertile pastures for UK law firms. After all, talk to UK lawyers about legal practice in the region and the recurring themes are optimism and opportunity.

‘Business is growing in all jurisdictions,’ the Gazette hears. English law remains the ‘law of major contracts’, a City lawyer reminds us. Another solicitor comments that London and Lagos are in the same time zone, which is convenient for everyone concerned.

Mining, infrastructure, telecoms and agriculture are increasingly supplementing the region’s traditional dependence on oil and natural gas, the Gazette is told.

El Dorado for England and Wales firms?

The old maxim that if it sounds too good to be true, then it probably is, comes to mind. Is west Africa really El Dorado for England and Wales law firms? It is not as though legal practice is in its infancy in the region. Nigeria alone has around 105,000 qualified lawyers and the country’s bar association – in common with those of its neighbours – regulates the profession in such a way as to disqualify outsiders from setting up in practice there.

As Africa becomes more important in global economic terms, working effectively with law firms on the ground becomes ever more necessary

David Church, DLA Piper

Nigeria is also home to the Lagos Multi-Door Courthouse (LMDC), Africa’s first alternative dispute resolution (ADR) centre connected to the national justice system. This not-for-profit body opened its doors to the public in 2002 with the aim of easing the pressure on the courts, which were chronically over-burdened with litigants pursuing what was previously the only accessible route to dispute resolution – litigation.

Cases, following appeals, could typically take between five and 20 years before the courts ruled on them. The LMDC, on the other hand, offers multi-faceted mechanisms, such as mediation and other forms of ADR, to provide more timely resolution.

Some 16 Francophone countries in the region, moreover, have come together to form an organisation for the harmonisation of business law in Africa; in some instances, this has meant modernising legal systems that date back to Napoleonic times.

In a nutshell, the law, as practised by local practitioners, is alive and well in the region. Which begs the question: Why the need for British lawyers? ‘Capacity’ is the answer.

Legal services in west Africa are still largely delivered by small firms based around a single named partner. Such firms do not have the capacity to handle major, often international projects, where massive corporations have contracted with governments for millions of pounds. There are sub-contractors to consider, complex finance deals, employment law issues, health and safety, penalty clauses and, above all, huge exposure to risk.

Common law legacy

That is where UK law firms come into their own. Local firms require the support of firms peopled by lawyers experienced in, for instance, mitigating risk to clients through cross-border arbitration. Fortunately, Anglophone countries in the region are still wedded to the common law legal system, retained on independence. UK law firms are the perfect match.

‘It’s not a gold rush,’ one UK lawyer concedes. ‘It takes work and patience before you can start billing and getting paid.’ Global firm DLA Piper international development partner David Church concurs. ‘Africa is a continent that rewards long-term commitment and understanding,’ he states. ‘As Africa becomes more important in global economic terms, working effectively with law firms on the ground becomes ever more necessary.’

A NATURAL FIT

On the credit side, west Africa has vast reserves of oil and natural gas. Nigeria, the continent’s most populous nation, ranks 10th in the world for oil reserves and ninth for natural gas. Ghana and Senegal, the latter with a predicted growth of 7% for 2018, are becoming ever bigger players in the exploitation of these same natural resources.

The region is also rich in gold, iron ore, uranium, diamonds, aluminium, nickel, phosphate, manganese and zinc. There are currently around 450 mining projects active in west Africa. Agriculture is similarly central to the region’s economy. The Ivory Coast is the world’s largest raw cocoa exporter. There are deep water ports and, directly westwards across the Atlantic, the lucrative US market beckons.

On the debit side, the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade – which began in the early 16th century – can still be felt. An estimated 11 million people were enslaved and shipped to the Americas from west Africa, of whom 1.4 million are believed to have died during the voyage across the ocean. This had the effect of stalling population growth, even reducing it, and has been blamed for the continent’s relative lack of economic development.

In modern times, the frequent fluctuation in the price of oil and gas has hit exporters, such as Nigeria, hard. The economic meltdown of 2008 was felt many thousands of miles away from London and Wall Street, with investment and prospecting for new deposits of mineral wealth put on hold in west Africa and elsewhere.

Respect and understanding

Church has worked across Africa for more than 20 years and has relationships with west African law firms spanning up to 10 years. Are there differences in the legal culture that complicate such relationships? ‘No more than when, say, Russians and Italians interact,’ he replies. ‘The key is respect and understanding. The same applies when a UK firm cooperates with, for instance, a Ghanaian firm.’

What about terrorism? Does Boko Haram deter investors? ‘We haven’t seen investors running scared,’ he says. A final question for Church: China has more than a million citizens already living and working in Africa. How big a threat does this pose to the UK’s expansion plans in the region? ‘China is a very important factor generally in west Africa,’ Church responds. ‘But there are still opportunities for us as economies diversify or expand.’ Fin-tech [financial technology] that aims to compete with traditional methods of delivering financial services, such as mobile banking, is developing well, Church notes, adding: ‘Well-established industries, such as oil, gas and mining, are constantly opening up in different parts of the country.’

There are cultural differences throughout Africa, as well as between Europeans and Africans. We have to be sensitive to the cultural background and work to make a positive contribution

David Greene, Edwin Coe

City firm Edwin Coe senior partner David Greene is less sanguine about China’s presence in Africa. ‘The Chinese may offer soft loans [a loan with a below-market interest rate and other concessions to borrowers], but they have no interest in human rights. They have even been using Chinese prisoners as the labour force on their Africa projects. That’s slave labour. And what’s more, by not recruiting local labour for their projects, they are doing nothing to enrich the local community’.

Greene has worked for around 25 years with governments across Africa. ‘The English law tradition is highly regarded in Africa and many now long-independent states still model their own laws on it. London is widely acknowledged as a global centre for legal excellence, all of which opens doors for UK law firms.’

Much of Greene’s work over the last quarter century attests to the depth of English law and how it can be applied not only to commercial usage, but also to human rights and civil justice. He has worked with governments in such areas as the transparency of the court system and legal aid. ‘In too many African states, women are still treated as chattels,’ Greene says. ‘After her husband dies, for example, a widow can be cast out on to the streets because she lacks property rights.’ He adds that, compared with corporate law, there are ‘no great rewards in this work, just the fascination of working with people from very different cultures and learning what’s possible and not possible’.

He has a warning for all UK law firms considering expansion into Africa: ‘As Europeans, we cannot expect to impose our standards and procedures wholesale into somewhere quite alien. There are cultural differences throughout Africa, as well as between Europeans and Africans. We have to be sensitive to the cultural background and work to make a positive contribution.’

The Gazette talks next with Segun Osuntokun, the managing partner of Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner’s London office. Osuntokun was born in Nigeria, but moved to England with his parents when he was 15. ‘The firm’s primary role in west Africa,’ he says, ‘is to look after the interests of our clients there. These could be west African clients, British clients, multinational clients or clients from anywhere in the world.’

Fast-growing market

Why west Africa? ‘It’s a fast-growing market,’ he replies, ‘and it’s important to have a foothold there.’ But is the market growing fast enough? Osuntokun, who confesses to ‘personal and professional reasons for taking a significant interest in Nigeria’, describes as ‘crazy’ the status quo where oil, the mainstay of the country’s economy, is exported in its crude form and then imported at great cost in its refined state as fuel. ‘It’s typical not just of the oil and gas industry in Nigeria, but also of many African economies.’ Close to Nigeria, for example, he cites Ghana, which is the world’s second biggest exporter of raw cocoa after the Ivory Coast, but has yet to develop an industry that produces export-quality fine chocolate.

Osuntokun returns to the subject of Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. ‘It’s been the next big thing for a very long time, but when is it going to become the big thing? If Nigeria develops the capability to refine the oil and sell it on the open market, the value to the economy will be huge.’ Help is on hand, he adds, as Aliko Dangote – a Nigerian businessman and, with an estimated worth of £9.1bn, the richest man in Africa – finances the building of a refinery in Nigeria.

Infrastructure upgrade

Osuntokun then points to the little known fact that Nigeria is a ‘huge grower of tomatoes’. Sadly, much of the crop is lost, he says, because of the lack of refrigeration and the inadequacies of the nation’s road and rail networks. ‘It’s a seemingly simple solution to fix, but building a refrigeration plant and upgrading the country’s transport infrastructure take time and huge investment.’

Global firm Hogan Lovells partner and head of Africa practice Andrew Skipper says: ‘You need to understand Africa, work in it, invest in it, and respect its lawyers.’ He adds: ‘If you’re not in Nigeria, you’re not in Africa.’ Why single out Nigeria? The country’s lawyers are ‘sophisticated’, he replies, ‘and at the high end, as good as any in the world’.

Nigeria has Africa’s biggest population, somewhere between 196-198 million, and is an economic powerhouse in the west Africa region. The mean age of its citizens is less than 18 years. Its development potential is colossal.

City firm Charles Russell Speechlys partner and Africa lead Adrian Mayer dismisses fears that investors in Nigeria might be scared off by the threat posed by Boko Haram. ‘Investors are savvy and invest wisely,’ he says. ‘The advance of Boko Haram has been checked by the government.’

And Mayer, who speaks with the Gazette just days after returning from a week- long business trip to Nigeria and Ghana, is upbeat about the future of Africa. The purpose of the trip, he says, was to visit clients and contacts. ‘Transactions are ongoing. It’s a continuing journey.’

Mayer adds that he has ‘always been confident for the future of Africa’ and that the trajectory is ‘upwards’.

Population growth

Kamal Shah, head of the Africa group at London-headquartered international firm Stephenson Harwood, has the final word. He is asked about Theresa May’s assertion, in a speech delivered in Cape Town, South Africa on 28 August, that at the present rate of population growth, Africa will need to create 10,000 new jobs a day simply to maintain employment at its current, and far from satisfactory, level.

He is unfazed. ‘The population of Africa is more than one-and-a-quarter billion,’ responds Shah. ‘Nigeria alone has a population of nearly 200 million. By the middle of the 21st century, Africa’s and Nigeria’s populations are expected to explode exponentially. Given those numbers, and in the context of a rapidly developing continent – with improving education, healthcare and infrastructure – the creation of millions of new jobs should follow naturally. But governments will have to keep this under review, or else the youth will vote with their feet to replace them.

‘Legal services in west Africa are keeping pace with this development. Local firms are commissioning consultants to advise on restructuring the partnership model so that the equity is spread away from just the one senior partner. There are now firms in Nigeria and Kenya with 100 lawyers, many of whom have worked in London or the US. Growing numbers of African lawyers are taking up secondments with firms such as Stephenson Harwood, which has been hosting secondees for a decade. The future is promising for Africa.’

This article started with expressions of optimism from UK lawyers. It ends with similar optimism for the future of a continent with vast natural resources, a young population and the drive to succeed.